Integrating Risk Management

Introduction

Over the last two decades, risk management in financial institutions has grown from being a part of the front office, to an independent, full-fledged functional department, covering all areas of risk – credit, market, operational, liquidity, asset-liability and interest rates – driven by the management adage “What gets measured, gets managed”. In many aspects, this development has been complementary to the efforts of the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision in assessing the capital requirements of global financial institutions, in quantifying their solvency, and estimating the likelihood of “black swan” events . However, risk management failures still occur with regularity – the recent past has seen sub-prime debt crises in Europe and America, sovereign debt crises in the Middle East and Eurozone, and rogue trading in UBS and Société Générale. In spite of the progress made in managing risk, the questions of “What is not working?” and “What still needs to be done?” are as relevant as ever.

Integrated risk management

The short answer to these questions is that further progress in integrating risk management is still needed. Currently, risk management practitioners have quantified a number of previous unknowns – in market risk, credit risk, operational risk, assetliability and interest rate risk – and are now turning their attention to more esoteric risks – liquidity, reputation, business, model risks – while bringing it all together under the umbrella of integrated risk management. How is this agenda evolving?

One approach has been to integrate risk management by increasing the complexity and scope of risk measurement – given how statistical and mathematical tools have helped us gain insights into market and credit risks, institutions are turning their intellect to applying these tools to more esoteric risks and business activities. How is liquidity risk measured? How are model risks quantified? What is the scope of business and operating risk? – are all part of the agenda of this approach.

A related approach to integrated risk management addresses what may be the most important question of all, arising from the agenda of the Basel Committee – how should loss distributions for different risks be constructed and aggregated, incorporating diversification between them, to arrive at a single figure indicating the overall solvency level of the financial institution? In response to this, institutions have sought to integrate and align their risk different measurement approaches – statistical models, simulation models, and scenario models – by aligning the model input scenarios, assumptions or parameters.

While these are worthy goals for integrated risk management, the history of risk measurement and management indicates that they would be difficult to achieve. Despite advances in risk measurement, we are no better at predicting risk, with financial crises occurring with frightening regularity in recent years, even when each of these have been described as a 5 standard deviation event, or equivalently, a 1 in 10,000,000 event. Quantifying solvency levels also have not resulted in safer institutions, looking at how seemingly well-capitalised institutions (at the 99.9% confidence interval standards of the Basel Accord and higher) toppled so quickly during the last financial crisis. While we have a better understanding of how financial risks behave under normal conditions, we still have not progressed very far in understanding how they behave under stress or extreme conditions. Going further along this path in building integrated risk management appears to yield diminishing returns.

A third approach to integrating risk management is pushing for greater application of the outputs of the risk management process. Already, leading financial institutions have begun to use risk management outputs actively in articulating the institution’s risk appetite, managing the capital base and setting risk limits. Following the recommendations of the Financial Stability Board , risk-aligned compensation practices will become more widespread and entrenched over time, and the concept of economic profit will become commonplace at financial institutions. This approach to integrating risk management with the day-today business of the institution, in line with a broader view of integrated risk management, is a more promising route for institutions to adopt, as it builds upon the part of risk measurement and management we know best – how risk behaves under normal conditions – and extends it into processes and actions which have tangible effects on the way risktaking is done. And this progress is not limited to the narrower risk and capital issues described above – the application of these techniques into areas as diverse as consumer banking, business approval processes, cost control and IT strategy have demonstrated the viability of this approach to integrating risk management.

Interestingly, much of what was considered risk management in the days prior to quantitative risk measurement and management, continues to be carried out within the business lines, for example, in structuring risk management solutions for customers, assessing the risk of individual and portfolios of customer transactions, hedging and risk mitigation, adjusting the risk profile of the investment portfolio or balance sheet, to name a few. These activities are some of the most important services provided by a financial institution. So in a sense, integrated risk management is already practised in financial institutions, only without much, if any, involvement of the formal risk management departments

An agenda for integrated risk management

To design an agenda for integrated risk management, it is useful to take stock of where we are currently:

- Risk management has focused on statistical risk measurement, especially in the tails of the loss distribution. Further progress along these lines is difficult, as we simply do not have enough historical data to address the most pertinent issues, such as why markets crash suddenly, or, what the transmission mechanism for contagion between different markets is, or, why correlations between risks increase under stress. Focusing on risk measurement as it is done today is unlikely to lead to significant progress for integrating risk management.

- There is increasing, but still inadequate use of risk management tools in daily management of financial transactions. The tools of risk measurement, grounded in historical data, have provided insights into how risk behaves under normal conditions. This has led to better risktaking decisions – in the estimation of expected credit losses and applying it to the design of credit approval, loan loss provisioning and pricing mechanisms, and in the estimation of the risks of a portfolio of assets or securities and using this to optimise the investment portfolio or balance sheet. However, this has not been taken far enough and across more activities.

- The increasingly specialised nature of risk management has resulted in a number of siloes within the financial institution. While each silo carries out some form of risk management, none of them working alone is as effective in managing risk as all of them working in concert, guided by the same objectives, and sharing the same risk information. In many institutions, risk strategy is crafted by taking the returns forecast by the business lines, and the risk forecast by risk management, regardless of what the risk models may indicate about returns, or what the market prices and customer behaviour may indicate about risk.

Taking these three points together, the future of integrated risk management lies not in pushing the statistical measurement techniques further to get a more accurate assessment of solvency, nor in stretching these statistical tools to cover more esoteric risks, but in looking for more holistic and relevant methods for assessing and quantifying risk, in refocusing on the areas where risk measurement can contribute to our understanding of both risks and returns, and turning these insights into tangible strategic and tactical recommendations for action with which to engage senior management and the business lines.

Rethinking risk measurement approaches

The first task for integrated risk management is to relook at the ways of measuring risk in a purely data-driven statistical fashion, aiming for ever more granular categorisations and at higher confidence intervals. Statistical techniques are very useful for organising and extracting insights from large masses of data, and these insights can be usefully applied for the daily management of risk, such as figuring out how market prices and rates move under normal circumstances, and the implications for hedging and structuring financial products. Once we move further beyond the centre of the returns distribution, the picture becomes less clear as to whether historical data and statistics has anything useful to tell us.

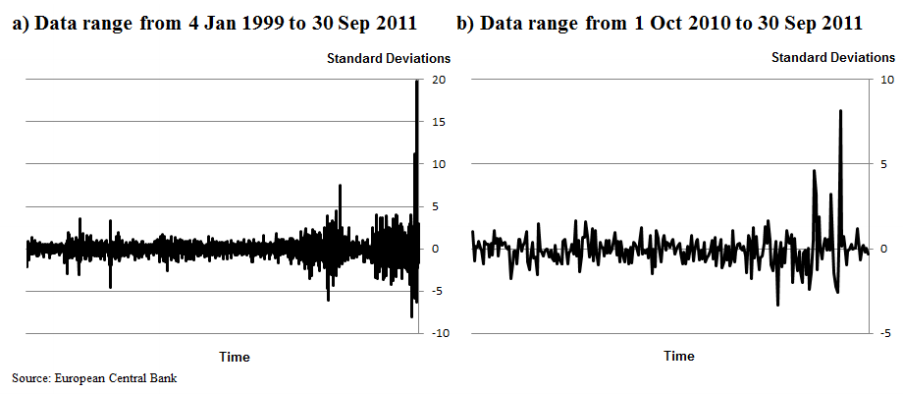

As an example, Figure 1a depicts the standardised daily fluctuations of the CHF/EUR exchange rate over the last 12 years, up until a 20 standard deviation event occurred on 6th September 2011, this being twice as large as any previous standardised movement in the CHF/EUR. In the statistical world where (log) returns are normally distributed, even if we took historical returns data from the last 1 year in Figure 1b, this event is a 8 standard deviation event, meaning that it is something unlikely to have happened since the universe was formed!

It is instructive that the first version of RiskMetricsTM (1994) for market risk specified a 95% one-tailed confidence interval (1.645 standard deviations) for measuring risk, recognising that there is only so much statistically extrapolating the tail of the loss distribution using statistics can do, even in a data-rich environment. Taking this any further, especially in the less data-rich environments for other risks would lead to less robust results. Rebonato (2007) also makes the same point.

This does not mean we should abandon quantifying the risk in the tails of the loss distribution – rather, it means we need to look at alternatives to statistical risk measurement. Integrated risk management should develop holistic approaches to building a better picture of risk, one not solely informed by historical data and statistics, but which incorporates views and data from markets, economic research, and customer and investor behaviours.

Figure 1: Standardised movements in the CHF/EUR exchange rate

For example, instead of generating aggregated risk and stress scenarios for the measurement of different risks from a catalogue of historical scenarios and data, how about generating scenarios consistent with risk management opinion, observed risktaking actions of the business lines and the customers and investors, and current market spreads and levels to figure out what may happen at the tails of the loss distribution?

Measuring what matters in operations

The second task for integrated risk management is to refocus efforts on quantifying and understanding the risk and returns which matter in running a financial institution – for example, what are the likely returns to a particular allocation of assets over the next three years? Or, what is the range of potential outcomes of an investment decision with 90% certainty? These questions, which are the crux of strategic business decisions, are questions which risk management should be able to provide insights to, and yet are seldom consulted on. By refocusing attention here, risk management would better contribute to the overall mission of the institution, and achieve integration of risk management with risk taking.

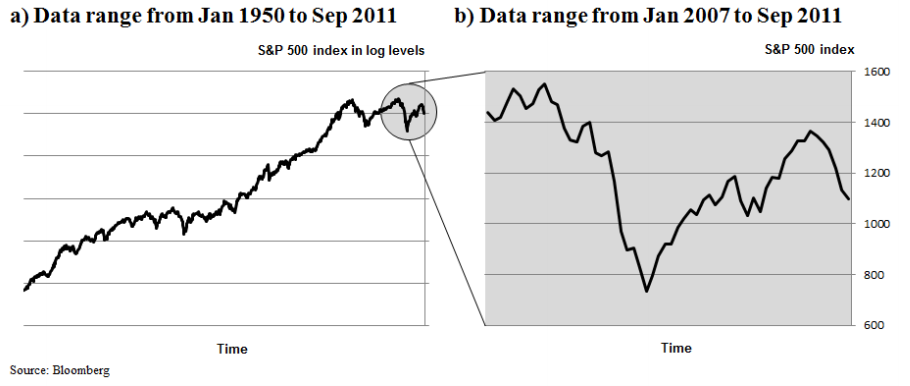

It is a rule of thumb that that the volatility of returns is more stable and predictable the expected returns, and for this reason, more attention has been paid to the estimation of volatility as a measure of risk, rather than to unreliable estimates of returns. Another common assumption is that the longer term trends or returns do not matter, as it would be swamped by the short term volatility in returns. As shown in Figure 2b, this is only true in the short term context of market risk, which is where most risk management techniques started from, but it is not true in the longer term as seen in Figure 2a, where the trend dominates. Would it not be more fruitful to focus on both risk and returns, in the short and longer term? Interestingly, Kim et al (1999) have laid out such a longer term agenda for estimating risk over longer term horizons, but so far this concept and forecasting of longer term expected returns, have not gained the traction it deserves.

The lack of insights on the longer term expected return and risks of different assets has meant that the contributions of risk management is restricted to higher-level strategic decisions only, like the risk appetite, capital management and performance measurement, and not in the day-to-day decisions around product and solutions structuring, hedging, and asset allocation. It is important that risk management is able to contribute on these topics to become a full partner to the business line, and achieving truly integrated risk management.

Figure 2: S&P 500 index

Engaging the siloes

The third task for integrated risk management is to integrate the various resources within the financial institution for risk management. As risk management became more specialised and sophisticated, it has grown from being incorporating market research, economics research, front office support and MIS, to a number of individual siloes, such as specialist units dealing with market risk, credit risk, operational risk, economic capital, stress testing, business risk, interest rate risk, assetliability risk, portfolio risk, and the list goes on. This fragmentation is not just within risk management. In a typical financial institution, it is not uncommon to also find risk units within the business lines, a portfolio risk department within the credit department, and market risk specialists within the trading department. There might also be several economic research units, catering to different customers, in the securities units and in the front office.

With this much brainpower focused on the different aspects of risk management, market and economic forecasting, it should be straightforward to harness them to manage risk better. However, at virtually all institutions, these differing units work at arms-length from each other, and rarely are their insights pooled, either for making better risk taking and management decisions, or to understand scenarios of the future, for stress and scenario testing.

Clearly, the opportunity for integrating risk management lies not in setting up more specialist units, but in simply consolidating the knowledge of risk and return already present within the institution. Each risk silo may currently have its own view and time horizon in defining risk and return, e.g. market traders focused on the very short term, economists focused on the long term equilibrium, and the risk managers somewhere in between. But some of the thorniest issues in risk management today are precisely about merging these different perspectives and horizons for an integrated view of risk and return.

To take the example of stress testing, while we are interested in the direct, short term impact of a shock to the financial environment, past financial crises show that large economic and financial shocks also occur gradually over time. In developing a set of stress and scenario tests, these different perspectives are useful ― what do short term movements in equity volatility and traded credit spreads tell us about longer term expectations in the market? How do quarterly forecasts of trade figures, inflation and GDP growth from the economics perspective help us understand the evolution of short term shocks into longer term scenarios? How do we reconcile the term structures of yields, spreads and risk in financial markets with the assumptions of risk and valuation models based on incremental diffusion processes?

Integrated stress testing

Stress testing has been an area of focus for integrated risk management at many institutions. Instead of using scenarios tailored for each particular risk type, resulting in a multitude of credit risk stress test, market risk stress test reports and so forth, integrated risk management works closely with each specialist risk and business unit to derive a series of general, macroeconomic or crisis scenarios, and uses these scenarios to generate the overall impact on the institution’s earnings and capital position across credit, market, operational, liquidity and other risks. This approach gives senior management a broad perspective on what could happen in such events under a consistent set of assumptions and inputs, rather than trying to work this out across several different stress test reports, each with different assumptions and inputs.

The power of approaching stress testing and scenario analysis in such a fashion has been clearly demonstrated by the Lehman crisis and the recent sovereign debt crisis, as credit, market and liquidity risks spiked in response to a common series of events. However, financial institutions still have not made full use of all the capabilities in the various risk management-related units. For example, in addition to the typical scenarios rolled out by risk management based on historically observed market price and rate movements, the different levels and term structure of credit spreads for sovereign debt in the recent European sovereign debt crisis convey market expectations about both the likelihood and timing of potential sovereign events, which can be incorporated into the design of the stress tests, helping to break away from the common assumption that the future should resemble the recent past. Similarly, the macroeconomic models of the economics research departments can be used to understand how such economic and financial shocks are transmitted between different industrial sectors in the economy, across borders, and over time and business cycles. Integrating these elements creates a set of stress test scenarios which are realistic in the sense of being aligned with the short term market expectations, and yet consistent with the evolution of the economy over time, something very rarely seen in most stress testing models.

Integrated balance sheet management

At the fundamental level, a financial institution carries out three major transformations – the maturity, liquidity and credit transformation of short term demand deposits secured with the institution’s credit standing, into longer term, illiquid and credit risky assets. It follows then, that the institution’s balance sheet and capital position, which is built upon these transformations, should be managed in an integrated manner across these dimensions. In this way, the institution would be able to meet its earnings targets by shifting the allocation and composition of the balance sheet, perhaps taking more credit and liquidity risk, and less interest rate risk, or vice versa. During the global financial crisis, the sharp increase in credit spreads allowed canny institutions the opportunity to reduce interest rate mismatch risk, while making up for this earnings shortfall through higher credit spreads and liquidity premiums. Other mismatches and transformations can also be found across the balance sheet of a financial institution, for example, currency mismatches between funding and lending currencies, and would also fall under the scope of integrated balance sheet management.

In most institutions, however, the credit, interest rate and liquidity aspects of balance sheet management are almost always run separately by different committees, for example, the credit committee and the assetliability committee. In some rare instances, some semblance of integrated management may occur, as a result of having a coincident set of committee members, who would be able to convey the decisions and views from one committee to another, but almost never by design. What this results in, is a less than optimal allocation of the institution’s most valuable asset – its balance sheet.

As markets, not just in tradable financial instruments, become more integrated and correlated with one another, an integrated approach to managing the balance sheet becomes a fundamental requirement for a well-run financial institution. This is a task, which by definition, requires the integration of insights on both the longer term risks and the expected returns of different assets, to ensure that assets and capital are allocated in a manner conforming to the institution’s mission, as well as the integration of the financial accounting and economic value perspectives, to ensure that financial control and liquidity are not sacrificed for short term paper profits. In other words, this requires integrated risk management across the business units, economic and market research, finance, and risk management functions.

Conclusions

In integrating risk management, changes need to be made in the way risk management is conducted – working as a partner to the various front, middle and back office departments, rather than being an independent cog in the machine, as a facilitator of differing opinions, rather than being the independent opinion on risk alone.

This approach to integrated risk management reflects the interpretation of the word “integrated”. Opting for a narrow definition means integrating risk measurement and management by enforcing a common set of statistical standards for measurement and management, looking to quantify and aggregate a common 99.9% confidence interval of the loss distribution across risks. Opting for a broader definition of “integrated”, as we have done, means integrating risk management into all aspects of the day-to-day management of the financial institution, using the power of holistic risk measurement and management tools to better structure, mitigate and manage risks, based on a detailed understanding of the risks and return from looking both at the past, the present and indicators of the future.